Exploring the Unique Ways Different Cultures Have Measured Time

November 12, 2024

Time is a fundamental aspect of human life, yet its measurement has varied significantly across different cultures and eras. From the ancient sundials to atomic clocks, the journey of timekeeping reflects humanity’s quest to understand and organize the world around us. This article delves into the fascinating ways various cultures have measured time, adapting their methods based on environmental cues, religious beliefs, and technological advancements.

1. The Origins of Timekeeping

The measurement of time dates back to prehistoric times when humans relied on natural rhythms. The obvious changes in the environment—like day turning into night or the changing seasons—served as the earliest indicators of time.

– Lunar Cycles: Many ancient cultures, including the Babylonians and the Chinese, based their calendars on lunar cycles. The moon’s phases marked the passage of time, with months defined as the time taken for the moon to complete its cycle around the Earth.

– Solar Calendars: In contrast, cultures near the equator, such as the Egyptians, developed solar calendars based on the sun’s position in the sky, which dictated agricultural cycles. The Egyptian calendar consisted of 365 days, segmented into 12 months.

This interplay between lunar and solar calendars remains evident in today’s hybrid calendars used worldwide.

2. Sundials: Early Mechanical Timekeepers

Sundials represent one of the earliest technological advancements in timekeeping, utilizing the sun’s position cast a shadow on a flat surface divided into hours. These devices were widely used by the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans.

– Egyptian Sundials: The ancient Egyptians utilized obelisks as towering sundials, marking the hours as the sun moved across the sky. These monumental structures were not only functional but also symbolic, representing the divine power of the sun.

– Greco-Roman Innovations: The Greeks improved upon the sundial by inventing a more precise version that used different shapes of gnomons (the part that casts the shadow). They were also responsible for calibrating sundials for various geographical locations.

The sundial, however, had limitations; it could not measure time on cloudy days or at night, which led to further innovations in timekeeping.

3. Water Clocks: An Innovative Solution

Water clocks, or clepsydras, represented another leap in timekeeping technology. These devices measured time by the regulated flow of water.

– Chinese Water Clocks: The ancient Chinese were renowned for their intricate water clocks, often featuring mechanisms that tipped water into vessels at specific intervals to indicate the passage of time.

– Greek Adaptations: The Greeks and later the Romans enhanced the design by adding gears and other mechanisms. They used water clocks in courts and public spaces to ensure fair measurement of time during speeches or trials.

Water clocks provided a more consistent way of tracking time, independent of sunlight, thus expanding the possibilities for timekeeping.

4. The Hourglass: A Symbol of Time’s Passage

The hourglass, with its two glass bulbs connected by a narrow neck, became a popular timekeeping device in the medieval era.

– Symbolic Importance: Beyond its practical use, the hourglass symbolizes the transient nature of time, often associated with mortality in art and literature. It represents the idea of time flowing inevitably, a concept central to many philosophical discussions.

– Cultural Variations: Different cultures adorned hourglasses with unique designs, incorporating pits for sand, colored glass, and intricate craftsmanship, demonstrating their artistic values and understanding of time.

Though not precise in the sense of modern clocks, hourglasses were a crucial tool in managing time across various activities, from cooking to conducting meetings.

5. The Pendulum: The Revolution of Accuracy

The invention of the pendulum clock in the 17th century marked a significant advance in timekeeping accuracy.

– Galileo’s Discovery: The pendulum’s potential for regular motion was first observed by Galileo, although it was Christiaan Huygens who built the first pendulum clock. This innovation allowed clocks to achieve unprecedented accuracy, reducing errors to seconds.

– Cultural Impact: The pendulum clock not only transformed personal timekeeping but also had broader implications for navigation and science. As societies became increasingly time-conscious, synchronized activities gained prominence, influencing everything from work hours to social interactions.

The pendulum’s significance extended to the scientific revolution, where precise measurements contributed to critical advancements in various fields involving timing.

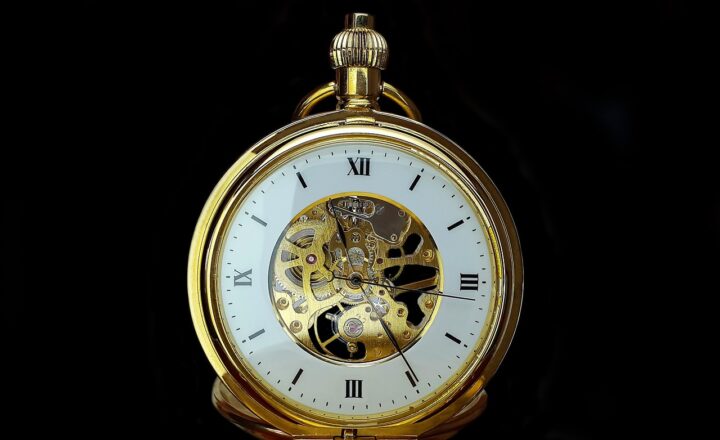

6. Mechanical Clocks: Timekeeping Becomes Universal

As mechanical clocks proliferated in the 14th century, they represented a turning point in the standardization of time.

– Church Towers: Large public clocks on church towers became symbolic of community time, signaling hours for prayer, work, and social life. The chime of these clocks served as temporal anchors for societies, helping organize daily activities.

– Cultural Adaptations: Different regions adapted clock designs to fit their cultural identities, with ornate designs in Europe reflecting artistry and craftsmanship, while simplicity defined many Asian clock styles. These clocks helped establish a more universal understanding of time across societies.

The advent of mechanical clocks transformed how people perceived time, embedding it deeper into daily life and influencing schedules and conformity.

7. Modern Timekeeping: The Atomic Age

The 20th century ushered in an era where atomic clocks became the gold standard for measuring time with unmatched precision.

– Definition of the Second: The definition of a second has evolved, now based on the vibrations of cesium atoms. Atomic clocks, accurate to billionths of a second, establish the timekeeping standard for international time zones and systems like GPS.

– Global Time: The interconnectivity of modern technology necessitated standardized time measurements. The adoption of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) promotes synchrony in an increasingly global society.

However, even amidst these advancements, cultural interpretations of time persist, from punctuality in Western cultures to more fluid interpretations in other societies.

Conclusion

The ways different cultures have measured time reveal much about their values, technological advancements, and environmental influences. As we have journeyed through time from sundials to atomic clocks, it becomes evident that timekeeping is not just about precision; it’s deeply intertwined with human culture, identity, and the natural world.

Understanding these diverse perspectives on time helps us appreciate the complexity of human experience and the universal need to impose order on the temporal flow of life. Although we live in an age of astonishing accuracy with modern timekeeping devices, the cultural significance of time remains a rich field of exploration, reminding us that our experience of time is as varied as the cultures that inhabit our planet.